When I was asked to share my experience as an Indigenous Youth, I felt both honored and reflective. I want to express my deepest gratitude to Anne, who has created a safe space for Indigenous individuals like me. Without her support, my story wouldn't be the same and I would not be sharing it with you here.

I am the descendant of a 60's Scoop Survivor and grew up in a non-indigenous adoptive family dynamic. I have many great memories of my grandfather who was from the Czech Republic, often spoiling the kids with sweet treats, a German grandmother who cooked big-wonderful family dinners, 3 silly uncles, and 6 cousins. But deep down, I always felt like something was missing. It wasn't just about my family dynamics; I struggled to fit in anywhere as an Indigenous person in a predominantly white community.

Watching my mother as a single parent I used to think she was an angry person, often taking her frustrations out on everything and everyone in her path, even me. Little did I know at that time that it was her own unhealed trauma from being separated from her culture, while also struggling without a sense of identity. I was aware from a young age that my mother was adopted and that we had no contact or connection with our Indigenous family. My mother had tried to form a relationship when she became an adult, but time had taken its toll and she was misunderstood. Often feeling like an outcast, she kept her distance and raised me with the help of my step-father, sheltering me from the heartache of not belonging anywhere.

When the government of Canada finally acknowledged the 60's Scoop and apologized for the wrongdoing, it was at that moment that I realized that all along something was not missing; something had been taken. I finally understood that my mother was a victim. This realization filled me with sadness but also became my driving force. I grew up with a burning desire to understand, and when I finally did, I made it my life's mission to heal and reconnect with my stolen roots, to be my mothers teacher and confidant for all that she had endured, and to break the cycle of intergenerational trauma for my family.

In 2015, I became a single mother and took a leap of faith and moved to Calgary with my then toddler and few personal belongings luggaged in garbage bags. I never allowed my dreams of living in a big city, becoming independent, and making my family proud dwindle. But life wasn't easy for me, just like many Indigenous people. I faced countless obstacles and hardships along the way, many of which I still do. However, I am grateful for my consciousness, my continuous efforts to improve, my focus on self-growth, and determination to break through the barriers that were meant to hold me back. I was able to get through the hardest times in my life by smudging, asking for guidance, and trusting that my purpose was bigger than my struggles. I found refuge in the company of my elders, becoming a sponge any time I listened to the stories, advice, and encouragement. I found my roots through ceremony and prayer, gratitude and appreciation from the lands, and a desire to learn my language.

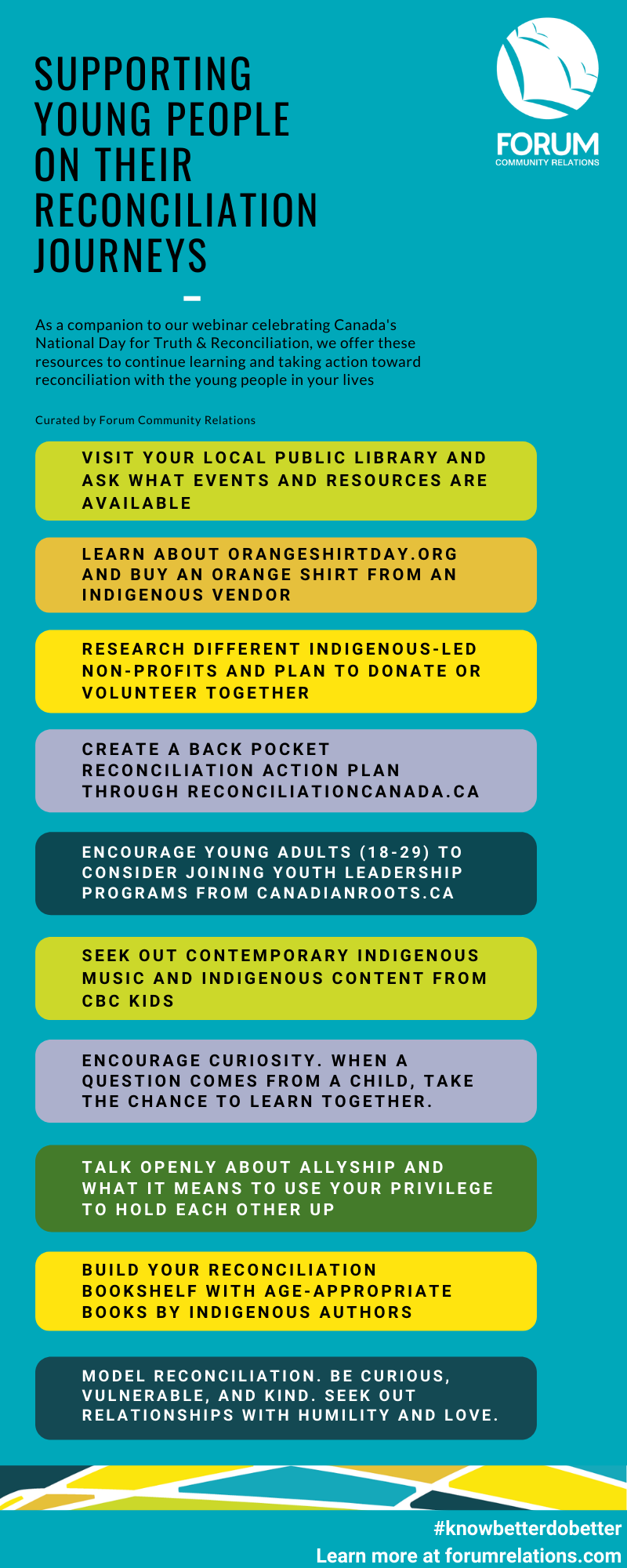

Today, I find purpose in helping others, being the advocate I once needed. I strive to be a friend, a mentor, and an inspiration to Indigenous Youth, especially to my 9 yr old son, and my 7 yr old niece whom I care for. I want to bridge gaps, connect people with support and resources, and contribute to Truth and Reconciliation.

When it comes to supporting Indigenous Youth, there is no one-size-fits-all answer. We face systemic challenges, intergenerational trauma, and the same day-to-day stress as anyone else. But what we truly need is unity and advocacy. Genuine and intentional friendship, and people that truly care to advocate and speak up for what is right.

My journey as an Indigenous Youth has been a rollercoaster ride of self-discovery, healing, and empowerment. By sharing my story, I hope to inspire others and contribute to the ongoing process of Truth and Reconciliation. Let's approach Indigenous Youth with sincerity, empathy, and a genuine desire to understand their needs. By building supportive relationships and providing opportunities, we can make a real difference. I'm forever grateful to Anne for believing in me, trusting me, and giving me a platform to speak on my experience and perspectives as an Indigenous Youth.

- Tenise Littletent / Ka’Katosakii (Star Woman)